December 02, 2020 by Quentin Read

Carbon footprint. For many of us, that term evokes cars belching exhaust and cows belching methane as they wait to be turned into hamburgers. But the carbon footprint of our digital infrastructure is enormous too! Data centers used approximately 1% of all electricity worldwide in 2018 and almost 2% of electricity in the U.S. There are efforts underway, including at the University of Maryland, to increase the use of renewable energy to power data centers, to recycle waste heat for beneficial uses, and to cool data centers more efficiently. Even so, power use by data centers is forecast to rise.

At SESYNC, we synthesize big datasets and crunch lots of numbers to fit models. This data-intensive work does not come without a cost. It requires many computer processors to run for long periods of time, consuming large amounts of energy. Some of this energy consumption, and associated greenhouse gas emissions, is unavoidable if you want to work with data. But if you are clever about the way you process and analyze your data, you can save significant amounts of energy and avert a non-negligible quantity of greenhouse gas emissions.

As most people reading this post probably know, the cyber team heavily promotes the use of R. R has a lot of advantages — it was designed for statistical analysis, it has a very active community of users and developers who are constantly cranking out new, cool packages, and it is relatively easy to learn for beginning coders. But one of its major disadvantages is that it’s pretty slow and memory-hungry. Both of those things mean inefficiency, and inefficiency equals high energy consumption. The main reason that R (and similar languages like Python) is so inefficient is that it is an interpreted language rather than a compiled one. An interpreted language is run line-by-line. This is the case whether you type the commands individually into the prompt or whether an entire R program is run all at once. Contrast this with a compiled language like C, where programs are written, compiled (translated from human-readable code into machine code), and run in their compiled form. The machine code is much more efficient, so compiled languages tend to be faster and thus use less energy, and on top of that, R is among the most energy-inefficient interpreted languages.

All of that is not to discourage you from learning R, but to give you additional motivation to optimize your code.

Recently, I found a major inefficiency in my own R code. I was doing a Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis, where I took 10,000 random draws from parameter distributions and repeated my analysis with each of the draws to estimate the uncertainty around the median result. Previously, I had been fitting a model within each iteration of the analysis, but I realized that I could save a lot of processing time by running a short script before the 10,000-iteration loop and using the results within each iteration. I was curious how much greenhouse gas emissions were saved in this process, comparing the final code I ran on SESYNC’s Slurm cluster with the unoptimized code I would have run. I was also curious how those emissions would compare to other GHG-intensive activities, such as driving a car, streaming Netflix, or eating meat.

I put together this information for a back-of-the-envelope analysis:

I’ll spare you all the calculations. The unoptimized code would have taken ~220 seconds (3:40) to run each of the 10,000 iterations, which is over 25 processor-days. The optimized code had an extra script that ran once on a single processor for ~18 minutes, but after that each iteration only took 2.3 seconds to run. So that’s around 7 processor-hours for the entire analysis, with setup included. The bottom line is that I saved about 606 processor-hours by optimizing the code!

How much electricity was saved, and what is the difference in terms of carbon footprint? Well, based on a few different sources, it looks like a single Slurm processor code draws somewhere between 15 W and 50 W when running a job. So let’s take the midpoint of 33 W. Then I used data from the Energy Information Administration1 to estimate that the average kWh of electricity in Maryland generates about 333 grams of CO2, mainly derived from natural gas, nuclear, and coal. (If we knew the exact mix of sources used to power Park Place, the building where SESYNC’s server lives, we might be able to get a better number there.) Based on those numbers, I estimate that about 6.6 kg (±3) of CO2 emissions were saved by optimizing the code!

Let’s compare the CO2 footprint of the energy saved with the CO2 footprint of some other activities:

For the car, we can use EPA’s number of 404 g CO2 per mile. For Netflix, it’s a bit more uncertain since there are a number of sources of emissions[^4]: the data center, the data transmission, and the device you are streaming on. The CO2 footprint of WiFi versus 4G is pretty different (much higher for 4G). Obviously larger-screen devices have a bigger footprint. Let’s use the weighted average of 70 g CO2 per hour across all modes of data transmission and whatever device you might use.

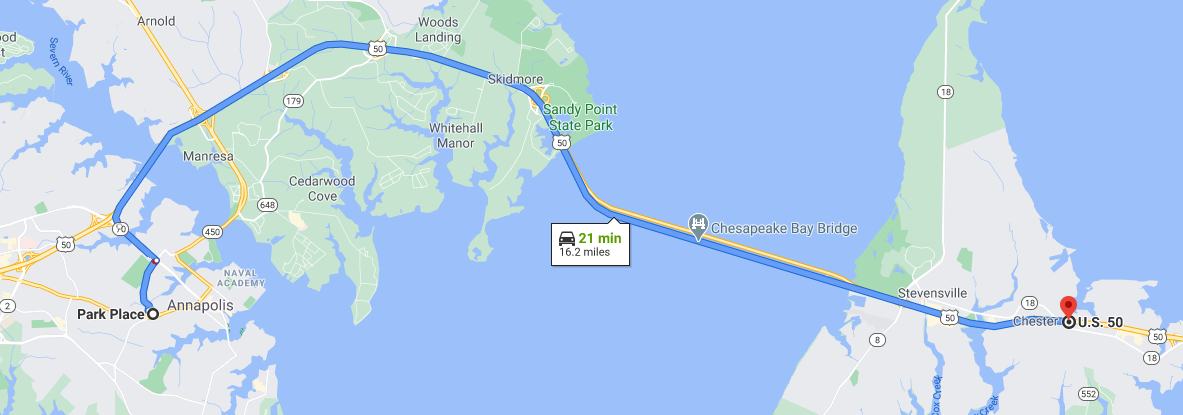

Assuming EPA’s number for GHG intensity of driving a passenger car, the amount of CO2 saved would get us 16 miles or 26 kilometers in a car. That would get you from Annapolis across the Bay Bridge and to the far side of Kent Island!

Using the weighted average across devices, with the CO2 saved from optimization, you would be able to kick back and stream Netflix for 94 hours, or almost 5 days straight. That’s almost exactly enough to watch every episode of “Great British Bake Off” ever recorded.

Plenty of time to mull over the controversy over whether Paul Hollywood’s babka was better than one from New York.

Producing a Big Mac requires about 4 kg of emissions[^5] so you’d only be able to produce 1.6 Big Macs with that amount of CO2.

I was surprised by the size of the carbon footprint of running code on the cluster. I hope this encourages people to sit down with their friendly neighborhood data scientist and look at ways to optimize their code and make it run faster and greener!

Here’s the GitHub repo where I show my work. Thanks to Kelly H. for providing some of the numbers!

This FAQ from the Energy Information Administration hosts two Excel files with the required data (total emissions generated by electricity in each US state, and the total electricity generated. Dividing the two yields GHG intensity.) ↩