January 13, 2020 by Quentin Read

This blog post will walk you through a quick example of how to use the rslurm package to parallelize your code.

SESYNC has a high-performance computing cluster which allows users to run lots of code quickly by splitting it up into many small parallel tasks and running them all at once on different processors. Many people in the SESYNC community could benefit from using the cluster to run big R jobs quickly. Unfortunately, submitting jobs to a cluster typically requires the user to know how to write shell scripts, which many SESYNC folks are unfamilar with. To fix that, the SESYNC data science team developed the rslurm package – problem solved! Now, SESYNC users can run big parallel jobs directly from the RStudio server. The code has similar syntax to an apply statement in R, so it will look familiar to users, and the whole workflow can be packaged inside a single R script – no pesky shell scripts cluttering things up! To read more about the rslurm package, visit the rslurm package website.

A common task that would take a long time to run sequentially but is easy to parallelize is finding the best values for tuning parameters for a machine learning model. This can become a very computing-intensive task because you often need to test many possible combinations of tuning parameter values. Within each combination of parameter values you might need to run a 10-fold cross validation, which in itself takes a lot of computing time since each cross-validation requires fitting 10 models. So if you have three tuning parameters to optimize, with only five different values for each parameter, you will end up with 53 or 125 cross-validations, or 1250 models to fit. Even if each model fit takes only 10 seconds that’s at least 3 hours.

Let’s take a look at how we could use rslurm to speed up the task.

The basic steps we need to take to do a parallel job in rslurm are:

slurm_apply() to run the parallel job.A dataset that SESYNC users might be interested in is the American Time Use Survey (ATUS). The ATUS is administered by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and measures the amount of time US residents spend on various activities during the course of a day. There are over 100 specific activities distinguished, that are divided up into major categories including things like paid work, childcare, and leisure activities.

We might be interested in whether we can predict demographic characteristics of individuals if we know how they spend their time. In this example, we predict individuals’ sex (male or female) given the number of minutes per day they spend on 17 groups of activities, using a subset of the ATUS data consisting of 5000 individuals.

You can download the toy dataset used in this example here. Load all necessary packages and read the CSV into R:

library(rslurm)

library(tidyverse)

library(caret)

library(gbm)

atus_sample <- read_csv('atus_sample.csv')

Here we have data on how 5000 people spent a day, with the number of minutes each person spent on 17 different activities, and their sexes. Here are the first few rows and columns.

atus_sample[,1:6]

# A tibble: 5,000 x 6

# sex caring_for_household_members caring_for_non_household_members consumer_purchases eating_and_drinking education

# <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

# 1 female 0 0 0 133 460

# 2 female 176 0 13 60 0

# 3 female 0 0 90 70 0

# 4 male 0 0 0 105 0

# 5 female 63 0 3 5 0

# 6 female 0 0 60 200 0

# 7 male 60 0 10 0 120

# 8 female 55 0 45 51 0

# 9 female 0 0 0 15 0

# 10 male 0 0 0 30 0

# … with 4,990 more rows

If you are interested in working further with ATUS data, the R package atus contains the full ATUS data for all years between 2003 and 2016.

Let’s go through each step of using rslurm to fit a model to these data to predict individuals’ sex.

When fitting a machine learning model, our goal is to do the best job of predicting test data that were not used to fit the model. There are many metrics for assessing the predictive performance of the model. Here we are sticking with a simple one: the prediction accuracy. An accuracy of 0.5 would be no better than random chance, and an accuracy of 1 would mean that the model predicts every individual’s sex correctly. We want to find the combination of tuning parameters that yields the highest accuracy.

In this example, we are fitting a type of machine learning model called gradient boosting machine (GBM). The model is implemented in the gbm R package, and we’re using the caret R package to tune the model. To validate the model we are using 10-fold cross-validation, meaning that we fit the model 10 times on a different 90% of the data and then test it on the remaining 10%. That way, we make good use of all our data but avoid overfitting to the training data.

Here is a function that takes a single set of tuning parameters and a random seed as arguments, then fits a GBM model to predict sex from activity times. We specify 10-fold cross-validation, so that for each fold it predicts the response variables of the 10% holdout dataset. Finally it averages the prediction accuracy across all 10 folds to return a single value of the model’s accuracy.

tune_model <- function(interaction.depth, n.trees, n.minobsinnode, random_seed) {

# This tells caret to use 10-fold CV to validate model

# Hold back 1/10 of the data, 10 times

fitControl <- trainControl(

method = "repeatedcv",

number = 10,

repeats = 10)

# Set a random seed so that results are reproducible.

set.seed(random_seed)

# This fits the model on our data using the specified tuning parameters and 10-fold CV

fitModel <- train(sex ~ ., data = atus_sample,

method = "gbm",

trControl = fitControl,

tuneGrid = data.frame(interaction.depth = interaction.depth,

n.trees = n.trees,

n.minobsinnode = n.minobsinnode,

shrinkage = 0.1),

verbose = FALSE)

return(fitModel)

}

We need to create a data frame where each column is an argument to our function and each row is an iteration.

Let’s test out three tuning parameters, the complexity of each tree interaction.depth, the number of trees n.trees, and the minimum number of individuals on either side of a split in one of our trees n.minobsinnode. There is an additional “shrinkage” or learning rate parameter which we will hold constant for this example.

Use the R function expand.grid() to make a data frame with each possible combination of 3 possible values for each of the 3 parameters. That means we will have 33 or 27 models to fit. Each of the 27 actually requires 10 models to be fit because of our 10-fold cross-validation.

tune_grid <- expand.grid(interaction.depth = 1:3,

n.trees = c(50, 100, 150),

n.minobsinnode = c(5, 10, 20))

Let’s add a column with a preset random seed for each run so that our results are reproducible:

tune_grid$random_seed <- 555 + 1:nrow(tune_grid)

Note that now the column names of tune_grid are exactly the same as the argument names of tune_model(). This means that rslurm can go through the tune_grid data frame row by row, each time using the parameter values from that row as arguments to tune_model(). If the names do not match, rslurm will throw an error!

head(tune_grid)

# interaction.depth n.trees n.minobsinnode random_seed

# 1 1 50 5 556

# 2 2 50 5 557

# 3 3 50 5 558

# 4 1 100 5 559

# 5 2 100 5 560

# 6 3 100 5 561

When you run an R script in parallel, you are creating a separate R environment for each of the tasks. You need to make sure that each environment has all the R objects needed to do the task. In this case you would need to make sure the environment contains the needed data and packages. By default, all the currently loaded packages are loaded within each of the task environments but you need to pass all objects explicitly. You can also specify just the packages you absolutely need if you want to speed things up slightly by avoiding loading a lot of unnecessary packages within each task.

For this example we need to make sure the data to fit the model is passed along, so we create a character vector with the name(s) of the data objects in our current environment that we want to pass to each task. In this case all we need is the single data frame with the sample of ATUS data.

data_names <- c('atus_sample')

We can also specify only the needed packages so that rslurm does not have to copy all the packages you happen to have loaded into your current R environment into each of the task environments. The packages required here are caret and gbm.

needed_packages <- c('caret', 'gbm')

Now we put it all together with a call to slurm_apply(). We specify the function name, the parameter data frame, a descriptive job name, the objects, and the packages. We also request the number of nodes to split the job across (only one is needed for this example) and how many CPUs per node. We request 4 CPU cores, meaning that this job will run about 4x faster than if you fit all the models sequentially. You can request more CPU cores if you have a bigger job. See the cluster FAQ for information on the number of available cores.

Optionally, you could use the slurm_options argument to pass additional options to specify things like the maximum memory and time allocation for the job, but that isn’t necessary for this relatively small job that we don’t anticipate hogging a lot of resources. The job scheduler will automatically assign the job to unused CPUs without you having to explicitly specify that.

Putting that all together, here is our call:

my_job <- slurm_apply(f = tune_model, params = tune_grid, jobname = 'tune_GBM', nodes = 1, cpus_per_node = 4,

global_objects = data_names, pkgs = needed_packages)

# Submitted batch job 2881

The message returned indicates that the job submitted to the cluster without any initial errors.

Off we go!

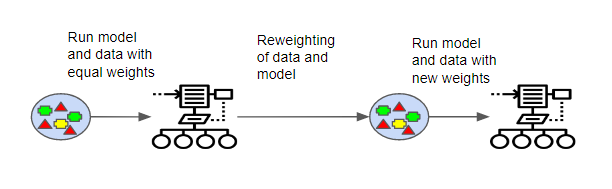

Boosting refers to generating a weighted average of a number of decision trees, and iterating the process repeatedly.

As the job is running we can call get_job_status() to see how things are going. Below is an example of what the output returned by get_job_status(my_job) would look like while the job is ongoing. The job has been running for 9 seconds.

$completed

[1] FALSE

$queue

JOBID PARTITION NAME USER ST TIME NODES NODELIST.REASON.

1 2881_0 dpart tune_GBM qread@se R 0:09 1 sesync03

$log

_rslurm_tune_GBM/slurm_0.out

""

attr(,"class")

[1] "slurm_job_status"

If the job has finished running, the output returned by get_job_status(my_job) would look like this:

$completed

[1] TRUE

$queue

[1] JOBID PARTITION NAME USER ST TIME NODES

[8] NODELIST.REASON.

<0 rows> (or 0-length row.names)

$log

_rslurm_tune_GBM/slurm_0.out

"Loaded gbm 2.1.8"

attr(,"class")

[1] "slurm_job_status"

If you are following along with this example code, the job should take around 5 minutes to run.

Once you have used get_job_status() to verify that your job finished without any errors, you can read the output back into your R environment using get_slurm_out():

tune_output <- get_slurm_out(my_job)

In this case we get a list where each element is a fitted model object:

str(tune_output, max.level = 1)

# List of 27

# $ :List of 23

# ..- attr(*, "class")= chr [1:2] "train" "train.formula"

# $ :List of 23

# ..- attr(*, "class")= chr [1:2] "train" "train.formula"

# $ :List of 23

# ..- attr(*, "class")= chr [1:2] "train" "train.formula"

# $ :List of 23

# ..- attr(*, "class")= chr [1:2] "train" "train.formula"

# <and so on ...>

Let’s extract the accuracy value from each element of the list using tidyverse code from purrr, a package for manipulating lists.

tune_results <- map_dfr(tune_output, 'results')

Sort the results so we can see which combination of tuning parameters results in the best model performance.

tune_results %>%

arrange(-Accuracy) %>%

head

# interaction.depth n.trees n.minobsinnode shrinkage Accuracy Kappa AccuracySD KappaSD

# 1 2 150 5 0.1 0.6639805 0.2951065 0.02037138 0.04293791

# 2 2 150 20 0.1 0.6637593 0.2948030 0.01729561 0.03654455

# 3 2 150 10 0.1 0.6637188 0.2950399 0.01742919 0.03657886

# 4 2 100 10 0.1 0.6635785 0.2928338 0.01712224 0.03637615

# 5 3 100 20 0.1 0.6624961 0.2931782 0.01834866 0.03878024

# 6 1 150 20 0.1 0.6623969 0.2881064 0.02029886 0.04266437

The best combination of tuning parameters is in the top row. However it looks like the model performance isn’t really that sensitive to different tuning parameter values, since we get an accuracy of around 66% across the board.

Make sure you save the output as .RData or write to a CSV!

write_csv(tune_results, 'tune_results.csv')

Once you’ve saved the output, you can delete the temporary directory that contains some files created by rslurm. The temporary directory is created in the working directory from which you called slurm_apply() and has the prefix _rslurm. It is not strictly necessary to do the cleanup, but if you are running lots of Slurm jobs, your working directory will eventually get cluttered with temporary files. Luckily, rslurm makes cleanup a snap!

cleanup_files(my_job)

All cleaned up!

Congratulations, you’ve successfully run a parallel job with the rslurm package!

post edited 25 Feb 2020, thanks Varsha for pointing out incorrect description of which model is being used.